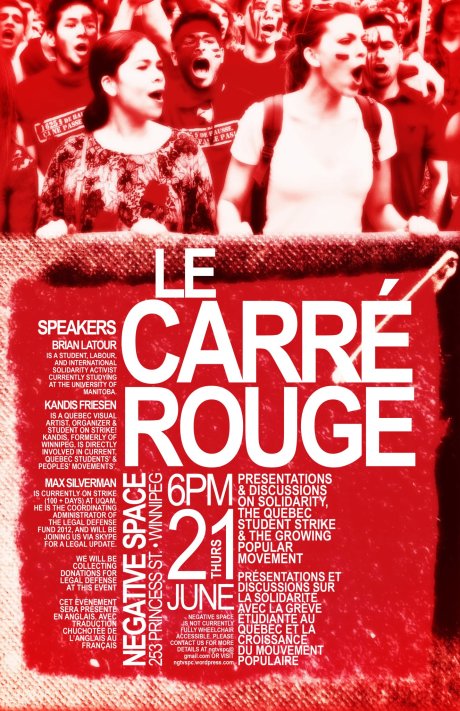

In September 2012, the Liberal government of Jean Charest was defeated, and the pro-independence Parti-Quebecois (PQ) was elected to a minority government. The PQ government almost immediately rolled back the tuition increase and repealed Bill 78-Law 14, the repressive emergency legislation to curb and limit public protest which had been introduced in May of that year. In the short term this is a victory and was certainly brought about by the mass protests during what has been described as Le Printempserable or Maple Spring. There is the amazing experience of the “carré rouge,” the small red squares worn by students and the general public that supported the struggle, the limits and missed opportunities.

By Aziz Choudry and Eric Shragge

In Quebec, students have a long history of battling against tuition increases and winning many of their campaigns, often through large mobilizations of students and strikes — shutting down departments and at times entire universities or colleges. The tradition continued in 2011-2012, but there were several differences. First, the scale of the strikes was larger, shutting down most of the French-speaking colleges and universities, with disruptions and confrontation in the English-speaking ones. These are public institutions. It would be the equivalent of shutting down public universities and colleges for three to four months. If viewed from this angle it is probably a unique situation in the North American context. Second, in previous years, demonstrations have been large and at times involved police and student confrontations and arrests. This time around, the mobilization was massive with several demonstrations estimated to have had more than 200,000 people on the streets. Further, for a period of more than 100 nights, downtown demonstrations disrupted the nightlife of the city, with escalating police violence in a futile attempt to limit the demonstrations. Nightly images on the news of police violence shocked many, as it was their family members, friends, and neighbours who were attacked with batons, boots, teargas, and pepper spray and who faced arbitrary arrest and detention. Third, at least partly because of the leadership of the left-wing students through their association CLASSE, La Coalition large de l’Association pour une Solidarité Syndicale Étudiante, and supported by excellent critical analysis, related research documents, and strategies of popular education for mobilization, the fight went beyond university tuition and became a lightning rod for broader opposition to the neoliberal direction that government policies had been taking over many years.

This became increasingly important as the student strike grew. Conservatives in the media and political figures on the right tried to cast the students as privileged and self-serving, but the links that the student mobilization made with the neoliberal agendas of the state resonated with the unions and the general public who were seeing an erosion of public services and benefits. Fourth, the street battles, mass arrests, and brutal police repression culminated in legislation designed to limit the right to demonstrate. This included suspending the school semester in striking universities and colleges, a move that then forced students back for an extra term in August and in some cases a double term at the beginning of September. The legislation was clearly an attempt by an intransigent government to exert some control over the situation. It soon became clear that the costs of the state’s repression – for extra police and an extra school term—far outweighed a negotiated freeze in tuition.

Charest’s liberal government clearly mismanaged the conflict and used repression as a clumsy tool to restore order. This too failed. The legislation was defied on May 22 by a demonstration of over 200,000 people who deliberately broke the law by not providing their route to the police. Some have said this was the largest act of collective civil disobedience in Canadian history. In neighborhoods and towns across the province, a spontaneous “casserole” movement took to the streets, people met outside at 8 pm nightly, banging pots and pans to defy the law. People gathered in numbers that defied the law limiting protests of more than fifty people and marched without permits or submitting pre-arranged routes to the police. Many who had never been active or had not been involved since their youth joined in demonstrations night after night. In some neighborhoods there were upwards of a thousand people. For example, in Eric‘s neighborhood one evening, over 200 people created a huge racket as they marched to the home of Premier Jean Charest, while the police directed traffic instead of stopping the march. Some people began organizing in their neighborhoods and convened popular assemblies in an attempt to broaden the opposition and further protest actions.

In this context, the government called an election and after a short campaign found itself in the opposition with its leader, Jean Charest, losing his seat. The new minority PQ government delivered on its promise to freeze tuition and repeal the repressive legislation. What are the lessons of this remarkable student strike? What are the factors that contributed to the success of this movement?

The first place to look is within the movement itself. As described in the previous article in Social Policy on the student strike, there were three active student organizations. Two are the formal bodies that represent the college and university student associations, FECQ and FEUQ. The other group CLASSE was constituted as a temporary coalition built out of ASSÉ, the more militant group, ideologically to the left. This coalition was created to counter the tuition increases, coordinate the mobilizations, and work through a form of direct democracy in which departmental assemblies that voted to strike would be affiliated with it. In previous strikes and conflicts, the government was able to provoke divisions between radicals and moderates. This time, partly because the government was so stubborn and heavy-handed, this did not happen to the same extent; there was solidarity between the different bodies.

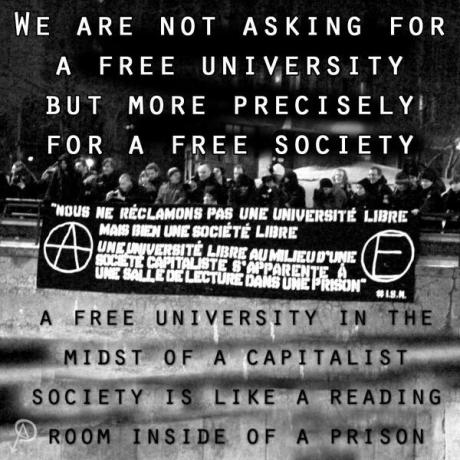

CLASSE took the leadership in organizing the demonstrations and was successful in both maintaining their base and advancing a process of democratic participation directly with the departmental student bodies where there was face-to-face discussion and debate. The combination of a decentralized participatory model with clear leadership that was accountable to the process strengthened the mobilization and permitted local activity. In contrast to many movements with a singular goal or others without demands — e.g. Occupy! — the leadership of CLASSE was able to stay focussed on its demand, a tuition freeze. But at the same time it had a longer-term program — free education — and put forward a deeper analysis of both the corporatization of the university and the neoliberal policies and direction of the state, at times providing an explicitly anti-capitalist analysis. Their position worked to politicize students and the public, find and build allies, and at the same time stay focussed.

A lasting lesson here is that sustained action, mass mobilization, smart leadership, and building good relations with allies can force change. With this mass organizing came the capacity to disrupt the normal functioning of the city and threaten tourism. Power came from the mass actions and the courage to withstand police violence.

Underlying this victory is a lesson about building and sustaining a base — one that can be mobilized — and showing support for the campaign. Without the local organization in colleges and universities across the province, the day-to-day activities required to keep institutions and departments closed would not have happened, and the mass mobilizations would not have had a base.

There is no shortcut; local work is essential. It is at this level that education and argumentation about the issues is best. This is how leadership emerges and how mobilization happens. A large part of the success of the student movement is owed to local organizing. Without local organizing, agitating, educating, and leadership-building, broader change is impossible — but, without “the movement,” bigger campaigns, alliances, and coalition building, local organizations cannot contribute to wider social change and can fall into insular activity, whether service provision or attempting very limited campaigns on very limited issues.

Some exceptional things about this period were the huge popular mobilizations that reached well beyond just students. For example, on 22 April 2012 — Earth Day – the combined efforts of students and environmentalists brought out 300,000 people. Police repression reinforced by the draconian laws — the “Special Law” 78-Bill 14 — further polarized this larger base, leading to the casserole movement and popular assemblies. These were short-lived, and as people began to engage in the election process, and with the defeat of the Liberal government, they petered out. It was a moment, though an exceptional and dramatic one. This is one of the problems of the intersection between popular resistance and large mobilization and engaging in electoral politics and gaining short-term victories. People go back home and return to the day-to-day, leaving the streets to cars and commerce. This example demonstrated the limits of spontaneous movements with very limited vision.

While conservative journalists and commentators were busy castigating the striking students for turning their backs on their educations, as educators working in universities in Montreal, we saw something quite different and profound happening. We saw a dynamic complementarity, as well as tensions, between formal academic education, and non-formal and informal learning in this struggle: from the teach-ins, to the student assemblies’ deliberations, to the formation of new student activist groups such as Students of Colour Montreal and the Graduate Student Mobilization Convergence at McGill among many others in both French and English universities. From and within alliances and networks forged across French and English language universities and colleges in Montreal, and in cross-campus anti-racist, feminist, queer, and labor discussions and actions which also connected up with other sections of Quebec society, student activism has gained new momentum through, and since, the strike. There are significant lessons about aspects of learning in/from this movement, which is now viewed internationally as a major site of resistance against the erosion of rights to education and the downloading of economic crises onto the middle and working classes for the benefit of economic and political elites.

Activist research played an important role in providing organizers with tools to argue against the tuition hike. A notable example is a brochure written in French by researchers at IRIS, Institut de recherches socio-économiques, and translated into English. This pamphlet debunked eight arguments commonly used to promote tuition-fee increases. It was distributed across campuses, adapted in many different leaflets and flyer forms, and posted online in both languages. Yet while websites and social media may have communicated information quickly, these were not the modes of organizing through which most of the education and mobilization work took place in building this movement. Two years of painstaking hard work through meetings, one-on-one or small-group conversations, collective organizing, methodical planning, popular education, and learning-in-struggle built this movement.

Without romanticizing, or even yet being able to assess fully the significance of the learning in the course of being involved in the student strike mobilizations, we believe this was often quite profound. These organization and education efforts themselves built upon the experience of earlier struggles for accessible education in Quebec. Learning and action went hand in hand in the general assemblies in which students organized the strike — debating ideas, framing arguments and counterarguments, making decisions, voting, building strategies and solidarity. This continued in teach-ins and other forums organized by striking students and in coalition work with other communities and movements to build connections and common fronts of struggle. It continued in anti-racist organizing within the student movement, challenging racism and the ongoing marginalization of many racialized students in Quebec. For a time, this climate of mobilization, political discussion, and collective action/learning spread to neighborhood marches, casseroles, and popular assemblies which sprang up across Quebec. But equally, with months of street demonstrations, every day/every night – incrementally, incidentally, informally, through talking, exchanging, marching together, claiming and creating space, confronting power, building solidarities and trust – there was learning that could not take place in a classroom.

This vibrant movement attests to the potency of “learning from the ground up.” A great deal of knowledge production, learning, and theorizing has taken place in this movement, often occurring under the radar of where we tend to assume learning and education to take place. Profound forms of informal learning may often be incidental and not even recognized as such, embedded as they are in social action. The massive numbers of arrests and violent police actions against protestors are hard to overlook. This movement was in turn infantilized, criminalized, and brutalized by the state and sections of the media, as well as attacked by university administrations and significant sections of university faculty. For many engaged in this struggle, such conflict has facilitated profound learning about state power, the legal system, and the way different people enjoy different rights within it, the interests reflected in the mass media, the limits of liberal democracy, and the commodification/corporatization of education. Moments of confrontation with authorities have often provoked rapid learning about the ways in which power in our world is socially organized.

Paula Allman (2001) suggested that “authentic and lasting transformation in consciousness can occur only when alternative understandings and values are actually experienced ‘in depth’ – that is, when they are experienced sensuously and subjectively as well as cognitively, or intellectually” (p.170). Perhaps we will not have to wait too long to see more clearly how lessons learned in the 2012 student strike are put into practice again. In February 2013, the most militant of Quebec’s student organizations, l’Association pour une solidarité syndicale étudiante (ASSÉ), announced that it would boycott Quebec’s higher education summit as provincial leaders refuse to consider the option of abolishing tuition fees and promised to mobilize a major protest on 26 February.

Finally, then, the Quebec student movement which built and sustained the 2012 strike was a rich site of critical learning both within the movement and outside, and one which reaffirmed the power and hard work of methodical organizing. Further, the level of engagement, sacrifice, and collective struggle which many thousands of Quebec students have displayed so consistently is forcing some to re-examine their cynical view of today’s youth as individualistic and self-absorbed. We cannot predict the course and outcomes of this movement, but the conscientization and politicization of a generation of students – and their courage in taking action – offers hope for the future for many people who do not see ‘business as usual’ as a viable response to today’s profound economic, political, and ecological crises. Indeed, perhaps as historian Robin Kelley (2002) suggests,

…the most powerful, visionary dreams of a new society don’t come from little think tanks of smart people or out of the atomized, individualistic world of consumer capitalism, where raging against the status quo is simply the hip thing to do. Revolutionary dreams erupt out of political engagement; collective social movements are incubators of new knowledge (p. 8)

[Notes: (1) This article first appeared in Social Policy

(2) We are also now on Facebook and this post is open to moderated discussion at:The Postcapitalist discussion]

End notes:

[1] Allman, P. (2001). Critical education against global capitalism: Karl Marx and revolutionary critical education. Westport, CT: Bergin and Garvey.

[2] Kelley, R. D. G. (2002). Freedom dreams: The Black radical imagination. Boston: Beacon Press.