By Poejesh

The following essay in no way represents KSU’s point of view on anarchism or Marxism. It is merely a personal opinion of one of KSU’s members. KSU is an open collective with no official affiliation towards Marxism, anarchism or other ideologies. This is the reason why within KSU we have a plurality of opinions. The following essay is only meant for internal discussion and polemics or for anyone interested.

The present paper has as its aim to show the nature, inconsistencies and the myths surrounding anarchism from a Marxist point of perspective, which makes it appealing to some people on the radical left. As is understandable this work will focus on the leftist, or more specifically anti-capitalist tendency of anarchism (libertarians, anarcho-communists, anarcho-syndicalism etc.); so anarchism will not refer in this work to those tendencies which are labeled as anarcho-capitalism (an extreme version of the neo-liberal policy where the state has no control whatsoever on the economic domain) or anarcho-primitivism and the like. Also the lifestyle anarchism which is popular among many leftist environmentalist activists with it’s own made up ethical imperatives (like veganism etc.) which are often imposed on others when they enter their domain (a very anti-democratic and authoritarian tendency from the chevaliers of ‘liberty for all’) will not be the focus of this work.

The purpose of this work is not to give an alternative to the anarchist ideology and movement. Alternatives already exist, whether from a radical left perspective or the bourgeois alternative of free-market capitalism. What I want to show is that given the premisses and implicit assumptions, anarchism will always be, as it has been historically, on the margins of the left and will not only be counter-productive but also dangerous to any kind of society in which the working class has gained the power i.e. socialism. The achievement of this goal will be done in more than one part. Part 1 will focus on the historical foundations of anarchism and its assumptions and why they are inherently false. Part 2 will focus on the more recent anarchist history with a focus on anarchist movements in the 20th century. Finally, part 3 will be a thorough analysis and critique of the present-day anarchist tendencies with their models of action and decision-making (for example the consenus-model, the affinity group structure of action etc.)

I will start by giving a short account of the origins of anarchism as a separate ideology and movement. I will focus on the founding fathers of anarchism in the nineteenth century. They will be divided in two groups: on the one hand we have the ideologues of anarchism, of which most of them didn’t call themselves anarchist or even anti-capitalist; on the other hand I will describe the forming of anarchism as a distinct ideology and movement in the 1860s and 1870s especially under influence of Bakunin. These accounts will not only be descriptive. On the contrary, the description itself will contain the critique.

1. The theoretical foundations of Anarchism: nineteenth century thinkers and the Proudhonian model

Before it’s appearance as a movement, the basic idea’s of anarchism had their foundations in the works of many nineteenth century thinkers, notably Godwin, Stirner and Proudhon. Although none of them explicitly called their views anarchist, except the use of the concept an–archy by Proudhon towards the end of his intellectual life, nor were they against capital in principle, they were able to introduce the idea of the abolition of the state, or antistatism in a new jacket. Antistatism was already existent in various forms. One could find antistatist ideas in the works of Adam Smith and other liberal thinkers where the state machine was seen as too much unproductive and a drain on civil society.

But it was Godwin, from whom for the first time a fully-fledged antistatist theory appeared on paper. Godwin sought the abolition of the state as the aim of society where the small enterprises were able to preform and compete without any restriction from the laws imposed by the state. It was the primal scream of the petty-bourgeois in a squeeze.

The pre-Marx socialism had always been defined by its hostility towards politics in general and politicians in particular. The main implicit assumption (which was never theorized) was that the state was the institution which defined the nature of society and not the other way around. According to Marx it is in fact the social relations of production and the cultural and historical context of the society which forms the state and its nature. It also assumed that the state only preformed negative functions and was a kind of cancer for society. State itself became synonymous to despotism and the antistatists weren’t able to see that the state had been a societal necessity in every class society and that it could preform positive functions as well. Furthermore, it was implicitly assumed that a state enjoying democratic freedoms was a nonstate. Neither was any alternative given for these positive functions in the form of an institution or organ which could preform these functions in a stateless society.

But none of the above mentioned ideas were seen as anarchistic. Since anarchism is indubitably antipolitical, it is sometimes assumed by a lapse in logic that early antipoliticalism was anarchistic. But the idea that the future social order would do away with the state was common platitudes of early socialism. Only with the publication of Striner’s The Ego and its own and the ideas of Proudhon, anarchism started to distinguish itself from mere antistatism which was even present in the ideas of Marx and Engels even before anarchism was known as an ideology.

Stirner’s famous book did have an influence, albeit a short one, on many antistatist radicals of the nineteenth century, most notably Bakunin. According to Stirner the Ego (the self, the I) was in its natural state when it wasn’t restricted by any external limitation. It was and had to be a sovereign of itself. The sovereign individual shouldn’t be restricted by social morality. Stirner’s contribution was in the end to carry the tendency of individual freedom and antistatism to a bizarre end: with Egoism unleashed, everything disappeared. His theory even rejected political and social revolution in favor of the ego-rebellion, and true to his principles he only observed the revolution of 1848 with a cigar in one hand and a glass of wine in the other: the archetype of the ego detached.

Another major contribution, one not so bizarre as Stirner’s, were the ideas of Proudhon. At the core of Proudhon’s theory lies the idea that the state is an unnatural phenomenon which restricts the individual. The alternative was it’s abolition and the creation of a Mutual Credit Society which would eventually take over society and give credits without any interest to every man for the purpose of investment. So the alternative for the bourgeois society was to make every man a bourgeois.

As stated above, it was not antistatism that marked anarchism as something new. It was something implicit (later made more explicit) in the ideas of Stirner and Proudhon: they put forward a particular rationale for their attack on the state by means of a line of thought about “authority”. It is the concepts of antistatism and authority which lie at the core of the anarchist ideology. Antistatism was already present in Marx’s writings of the 1840s. But the main difference with the more an-archic tendencies was that for Marx the ultimate aim of the revolution was the withering away of the state. For Proudhon and the like it was the first word of the revolution. This is a great and significant difference. According to Marx it is the class structure of society along with the social relations of productions which gives the state its essential features and structure. So we need to have a transient period where the class antagonisms are abolished and the function of the state is only the management of the production and it is only then that the state will wither away. There is no need in a classless society for one class to use the state as the repressive mechanism for its rule of another.

On the contrary, for Proudhon, and to some extent Stirner and Godwin, it is the state which lies at the root of all evil. State itself is the synonym of despotism and it is only through the immediate abolition of it, that society in general and the sovereign individual Ego in particular is able to be free from every facet of authority. Implicit within this approach is that the state precedes society and class structure, not the other way around. There is no need to explain why this approach is false, because it has been done by many writers.

Before we go on to the section on the formation of anarchism as a movement by Bakunin, it is noteworthy to draw some conclusions for the sake of clarity. First and foremost it is clear that the idea of antistatism itself existed long before any anarchist movement or ideology was present. So it is not antistatism that defines anarchism. Rather it is the combination of antistatism with the rejection of authority which is characteristic of anarchism even to our own day. The inconsistency and falsity of the anti-authoritarian stance will be given a thorough analysis in the next chapter.

Secondly, anarchism need not be an anti-capitalist ideology as it was not for Godwin, Stirner or even Proudhon. Only with the ideas of Bakunin, building upon the mixture of Proudhonianism and socialist elements which created an anti-capitalist anarchist tendency in the 1860s. It is to this episode that we now turn.

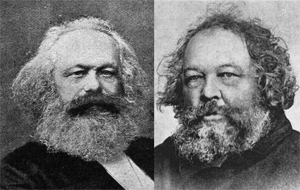

2. Bakunin and the illusory anarchist creed: “immediate abolition of the state and all authority“

Michael Bakunin could be seen as the founding father of anti-capitalist anarchism. For this purpose he combined three ingredients, loosely mixed:

-

A social theory based on the ideas of Proudhon and Stirner.

-

A socioeconomic program which was a version of the anti-capitalist collectivism current in socialist circles, including borrowings from Marxian theory.

-

A political strategy characterized by conspiratorial putschism, mixed with a kind of Russian-accented terroristic nihilism.

These ingredients will be changed in the twentieth century by the forming of other anarchist tendencies, especially the anarcho-syndicalist one, but many of the essential elements will belong to nearly every anti-capitalist anarchist movement.

2.1. Authority

Authority, or the imposing of the will of an individual or a group (whether the majority, an individual or something between) on another, was the main concept in Bakuninist rhetoric. It was authority which should be abolished because of its restriction over the sovereign individual Ego. By this creed authority came to be seen by the Bakuninists as principally wrong and evil. This meant in practice that even as soon as a workers state was established by revolutionaries, the anarchists would set out to destroy it from within or without (for example the many anarchist uprisings during the civil war in Russia). Anarchism in this sense would become destructive to the working-class movement.

By the principle of authority, the consistent anarchists means the opposition of any kind of authority, even authority derived from the most complete democracy and exercised in completely democratic fashion. Indeed, democratic authority is one of the most evil forms of authority for the anarchist. So anarchism is fundamentally antidemocratic, at least in its initial form. But the question remains: what to do when people disagree in a society where there is no authority and where individuals have to live in concert? How do you decide what a social group is to do in an organized society? No anarchist thinker, even the recent ones, has answered this elementary question.

The common anarchist view is best illustrated by the analogy of the ant colony. When the state and all authority have been abolished, society will come to its natural form like an ant colony and will come to an automatic consensus in some way and be able to organize society. This is nothing more than assuming that there is something like a “magic unanimity”. To anyone who needs this nonsense refuted, we have nothing to say here. We only should point out that this “magic unanimity” is almost always the decree of totalitarian states.

So what then if people disagree? Humanity has devised various mechanisms to cope with this problem in society: whether an leviathan decides for society or a small number of rulers, or the majority makes this decisions from below, there have been many used models in history. For all of the complexity of this problem, anarchism turns it into a vulgar simplicity: abolish every authority in order not to impose social decisions on a single sovereign individual, let alone a minority who disagrees. This tendency is also visible in the recent adopted models of decision-making like the so called consensus-model where the dictator of the minority is made possible under the totally false assumption of total democracy and having a decision based on everyone’s opinion.

So anarchism rejects both democracy and despotism and tries to find a third alternative which does do away with authority but somehow magically permits society to exist. Needless to say that no such device has ever been found. Authoritarian, as involving authority, is now turned into a synonym for ‘undemocratic’ and ‘despotic’. It is interesting to see how all of these catchphrases were practiced by the paladin of liberty, Bakunin himself. To that we will come shortly.

The main historical and theoretical objection to the above anarchist theory is visible when we look at the way in which social production is organized. All social production, all cooperation in labor, indeed the very meaning of cooperation, involves the labor of supervision in some form, hence the existence of some authority (not a despotic one). This is only needed for the directing of the process. One can make the despotic aspect of this authority disappear by making the supervisors or managers directly chosen and controlled by the laborers themselves instead of representing capital.

Another way to demystify authority is by simplifying politics and the state machinery, and making the very source of authority itself transparent. This is a precondition for an effective control from below.

. . .

By now the meaning of the word authority was changed by the false assumptions of the anarchists. Moreover, what the anarchist alternative advocated was in reality the atomization of modern society into fragmented parts with no real interrelation among them (no authority or centralism but all kinds of councils). It is more of an irrelevant utopianism of a backward kind. This position was not only impractical an destructive, it was basically anti-democratic; by opposing any kind of authority, even “authority with consent” (the authority of majority over minority) it upheld the right of a small minority to impose its conceptions upon the majority, even by violence. This is exactly the what Bakunin was to do with the International and his (Bakunin’s) secret Brotherhood by their “Rule or Ruin” creed.

By stating that every individual or group should be autonomous the anarchists cannot answer how a society of even two people is possible unless each is willing to give up some of his autonomy. This is a question for which there is no definite answer in the anarchist literature. Is any organization actually possible without authority (or the full autonomy of its members)? Take again for example a factory where the workers decide about the working hours. Whether this is done by a delegate chosen (and able to be recalled) or by the majority of the workers, the individual will (of for example one individual or a couple of them) must subordinate itself to this decision for production to be possible. So the questions are settled in an authoritarian way.

To prevent any misuse of the authority given to the decision makers, again whether the representatives or the majority, we can democratize the delegation of authority and make their activities totally transparent. But we cannot prevent some degree of imposing the will of this majority on the specific individual. What we can do, and must do, is to restrict authority within the limits enforced by the necessities of production of social life. If the anarchist is consistent he will even oppose this. But if he is not a lunatic (and we find lunacy in many anarchist movements throughout history) he will have to admit that not every individual Ego can be satisfied.

Even revolution itself is an expression of authority. It is often a conscious part of society, which hopefully represents the interests of the majority, that has fulfilled the task of revolutionizing society. Never in history have we had revolutions in which the majority itself actually took part in it. And this doesn’t seem plausible either. Revolution is in the end the imposing of the will of a class on the ruling one, and it is exactly this that defines authority. A truly popular revolution can impose a democratic authority, which of course anarchists oppose on principle.

More importantly, we have to realize that autonomy and authority are relative things whose spheres vary with the various phases of the development of society. It is by no means possible to do away with them right after the revolution. Only by an development of society towards the end of class antagonisms it is possible that those “evil” things could be done away with. But to go on the details would be mere speculation. It is up to the future man to accomplish this task, not our fantasies.

2.2. An example of anarchy: Bakunin

As Bakunin is favored by many leftist anarchists as one of the founding fathers of anti-capitalist anarchism, and indeed like stated above it was Bakunin who first created an anarchist movement, it is useful to shortly review Bakunin’s own practicing of the anarchist idea’s of the immediate abolition of the state and authority. The contemporary anarchists are in no respect held responsible for his actions, and it is not my goal to blacken them by means of Bakunin’s practices. What I want to sketch is that in reality, and not in the realm of utopianism, anarchism cannot do otherwise, at least not in essence.

Bakunin was from the start a putchist who had an Prhoudhonian Stirneristic outlook of the world. So for him the way to accomplish the stateless society was by means of a secret society of revolutionaries, called the International Brotherhood, with no more than one hundred members (according to him this was more than enough for the Brotherhood to take over the world) whose identities were secret, and it was they who would make the revolution and realize anarchy.

What about authority inside this movement? From the start on it was obvious that the sole authority of the movement was Bakunin himself. It was only his ideas and his ways of doing things which were allowed. He even imposed capital punishment for whoever interfered, even among his own ranks, with the revolutionary communes of Lyon, where he was present and hoped to start with the foundations of the anarchist society. As there was no democratic sanction, or one desired within the movement, Bakunin’s own despotism was obvious. This manifested itself with his ad hoc decisions for the Brotherhood.

Also his activities inside the International were of the same essence. Bakunin first agreed, on Marx’s insistence, to enter the International. But as soon he entered he created a faction within the International called the International Alliance of Socialists. The only practical activity of this Alliance was the constant harassment of the General Council of the International (for example the demand of the Alliance to clear the hall at the Hague congress at the moment were the members were voting). Being true to their creed of “Rule or Ruin” the Alliance tried to take over the International. As the responses were not in their favor they began the process of its ruination. It is one of the marvels of the anarchists to call the defenders of democratic authority (for example Marxists) “authoritarian” while the autocratic perpetrators of the typical Bakuninist putsch are ticketed as “libertarian” and the paladin of Freedom. What a great illogical imagination anarchists have.

Seeking to ensure the Freedom of the sovereign individual Ego, Bakuninism in operation meant the imposition of its own authority in autocratic forms: the establishment of a special sort of despotis by a self-appointed secret elite who refused to call their dictatorship a “state”. One could not imagine a more rigidly centralized, authoritarian revolutionary organization formed strictly from the top downwards than the one Bakunin proposed, for carrying the destruction of authoritarianism. We see that anarchism in its first experiment was transformed into its logical opposite.

There is a lot more to say about the Bakuninist experiment, but be that as it may, it is interesting to point at the inconsistencies of the fathers of anarchism and how they are viewed by some anarchists today to be the example of a good revolutionary. We haven’t even talked about Bakunin’s ridiculous activities in Sweden (his flirtations with the king of Sweden where he championed constitutional monarchy in a speech) or the Bakuninists in Spain (by participating in a bourgeois controlled government in 1873).

2.3. The state

Anarchist theory of the state is a very simple one, and we have already mentioned it above, namely: it is the state, and all political life, which is the devil and has engendered all social ills. The complexity of reality, as well as the positive tasks of a state together with the potential of the state not to be a despotic one, are simplified and vulgarized in the anarchist thought. They do not regard capital, i.e. the class antagonisms between capitalists and wage-laborers which itself has arisen through social development, which gives the state its specific characters. It is as if the state has created capital and that the capitalist has his capital through the grace of the state.

If the state is the source of all social ills, it is by its abolition that capital will magically vanish. According to Marxists do away with capital, the concentration of all means of production in the hands of the few, and the state will fall of itself. Despite the great number of historical and theoretical refutations of the anarchist position about the state, the “immediate abolition of the state” is the product of pure dogma, simply an unhistorical view of the relation between the state and the social order.

The alternative of the present day anarchist, is the breaking up of society in small groups, communes, councils etc. which in turn form an “association” but not a state. What the difference is theoretically, no one knows. But lets not call it a state, as if a name changes anything about the essence. Fooling yourself and others could be propagandically useful but not when one tries to organize a society. These are nothing more than the idealist fantasies of the “libertarians”, and nothing more remains to be said about this vulgar, simplified and caricaturist conception of society.

3. “Anarchists, know thy history and theory”

So lets conclude this essay by some final words. We saw that antistatism was something that existed long before the anarchist movement came to existence and was nothing new. The new dimension which anarchism gave to the discussion was the discussion of authority, which should be abolished in all of its manifestations. By this the state = authority = evil. There is no non-despotic state possible. So the first word of every movement and revolution should be the abolition of these two evils.

For the Marxist on the other hand the “abolition of the state” could about only at the end of a sufficient period of socialist reconstruction of society. So when a socialist government takes power, even in its most democratic form possible, the consistent anarchist must seek its instant destruction as an “authoritarian” menace. But this very act itself is somehow magically not authoritarian. Inconsistencies drip of anarchism in theory and practice.

Secondly, for Marxists the aim of the socialist movement is the democratization of political authority, indeed of all authority. For an anarchist, any and all authority, however ideally democratic, has to be destroyed. For Marxists, the abolition of state power does not necessarily entail the elimination of all kinds of authority (for example the authority of the head-engineer of the railroad, or the head surgeon of a hospital) in political and social life. But it is possible for society to evolve in the direction of the diminution of authority in general.

Last but not least, the difference of anarchism and Marxism lies in the definition of freedom. For the anarchist freedom is basically individual–solipsistic: it depends on the absolute inviolability of the sovereign Ego in relation to the outside world; it is the total impermissibility of any imposition of any authority. So anarchism is basically solipsism, whether or not the individual anarchist recognizes this consciously (as I am of the opinion that many anarchists do not). Freedom does not mean freedom through democracy or freedom in society, rather freedom from any democratic authority and in the end freedom from society.

The Marxist view of freedom is basically social in its reference. Freedom depends on the relation of the individual to his membership in the human species, which is historically organized in a society. Freedom is than the democratic freedom in society. This means that the relationship of the individual to the collectivity will involve the maximum extension of control from below. This control applies also to the determination through democratic institutions of the extent or degree to which the collectivity of society should exercise any control over its individual components.

In conclusion, for Marxists (classical)anarchism is not a beautiful vision of saintly dreamers but a sick social ideology. Not only impractical but dangerous in certain contexts (like when there is an actual workers government established). To the anarchists we have only, in the words of Plekhanov, this to say: “You will remain what you are now… bags emptied by history.”

Kameraden,

Ik heb waardering voor de KSU. Het is een open organisatie waar iedere student, scholier (en volgens mij zelfs afgestuurden) aan deel kan nemen c.q. lid van kan worden. De KSU is onafhankelijk, wat wil zeggen: dat ze aan geen enkele politieke organisatie ondergeschikt is en diens directieven zou moeten opvolgen. Heb ik gelijk of niet?

In die zin is de website van de KSU ook een open forum, waar iedereen – zij het op een fatsoenlijke, waardige wijze – zijn of haar mening naar voren kan brengen. Het is dan ook heel gewoon dat er nu ook een eerste deel van en artikel op de website van de KSU verschijnt, dat een marxistische kritiek levert op het anarchisme. Ik zal eerlijk zeggen dat ik nog niet de gelegenheid gehad heb om het goed te lezen. Maar ik zal dat ongetwijfeld gaan doen.

Wat me echter het meeste bezighoudt, is niet zozeer de inhoud van het artikel, dat waarschijnlijk op voor een groot deel een terechte kritiek levert, maar de vraag: waarom verschijnt het juist nu op de website van de KSU? Op een moment dat er een poging gedaan wordt om de KSU en de ASB (een anarcho-syndicalistische groep) en de IKS samen te brengen in een activiteit van solidariteit met de huishoudelijke hulpen uit Haarlem en de IJmond, die massaal bedreigd worden met ontslag? Op een moment dat we samen (de ASB incluis) een solidariteitsverklaring uitgebracht hebben ter ondersteuning van hun strijd? Zijn de kameraden van de KSU op de hoogte van de ernst waarmee de ASB, (die zich anarcho-syndicalistische noemt) haar taak op zich neemt? Wat te denken van het pamflet tegen de oorlog in Libie, dat de ASB heeft gepubliceerd en dat is overgenomen van KRAS uit Moskou en dat overigens ook op de website van de IKS is verschenen? Zijn de kameraden van de KSU op de hoogte van de brochure van ASB, “Introductie tot klassestrijd en revolte” (http://anarcho-syndicalisme.nl/wp/?page_id=814). Een boekje dat de Internationale Kommunistische Stroming besproken heeft in haar laatste nummer van Wereldrevolutie?

De solidariteitsverklaring met de huishoudelijke medewerkers is een serieuze kwestie. Het is geen ganzenborden wat hier gebeurt. Het is een doodernstige zaak, waarbij mensen van vlees en bloed, onze klassebroeders, door de dreiging met ontslag, op een mensonwaardige wijze behandeld worden. Het kan niet anders gezegd worden dan dat de ASB, door haar deelname aan deze solidariteitsactiviteit, een hele verantwoordelijke houding aanneemt. En het interesseert me dan geen zier of ze zich anarchistisch, autonoom, anarcho-syndicalistisch, vrij socialistisch, vrije communistische of wat dan ook noemen. Het gaat om de verbondenheid in de strijd van allen die getroffen worden de gevolgen van de crisis van dit systeem.

arjan de goede

I think the author of this article has some fundamental misunderstandings about anarchism. At the outset of the article the purpose was to elaborate on “early” anarchism represented by people such as Godwin, Stirner, Proudhon and Bakunin. This is done in some fashion in the first chapter, however in the second part on authority (2.1), many sweeping assumptions about anarchist theory and practice are made that underscore a weak understanding of anarchism in general, and are not based on writings of the above mentioned authors. This is a shame and would lend the arguments some strength, which they do not have now in the current argumentation.

“There is no need to explain why this approach is false, because it has been done by many writers.” – go ahead.

“Anarchism in this sense would become destructive to the working-class movement.” – on the premise that the Bolshevik party dictatorship had anything to do with “the working class movement”

“By the principle of authority, the consistent anarchists means the opposition of any kind of authority, even authority derived from the most complete democracy and exercised in completely democratic fashion. Indeed, democratic authority is one of the most evil forms of authority for the anarchist. So anarchism is fundamentally antidemocratic, at least in its initial form. But the question remains: what to do when people disagree in a society where there is no authority and where individuals have to live in concert? How do you decide what a social group is to do in an organized society?” – this whole paragraph mixes up the liberal democratic form of government and the principle of “democracy is the will of the people” a common mistake but still.

“No anarchist thinker, even the recent ones, has answered this elementary question.” – This just isn’t the case (think of Kropotkin or Bookchin for example), and belies the authors lack of knowledge of anarchist theory.

“The common anarchist view is best illustrated by the analogy of the ant colony. When the state and all authority have been abolished, society will come to its natural form like an ant colony and will come to an automatic consensus in some way and be able to organize society. This is nothing more than assuming that there is something like a “magic unanimity”” – this obvious straw man argument just doesn’t reflect common anarchist views, which for example propose to build institutions based on solidarity, freedom and mutual aid inside the current society.

“For all of the complexity of this problem, anarchism turns it into a vulgar simplicity: abolish every authority in order not to impose social decisions on a single sovereign individual, let alone a minority who disagrees.” – Have you heard bottom up direct democracy, federalized on organized on a larger scale with recallable “representatives”. A model that many left Marxists would adhere to as well.

“All social production, all cooperation in labor, indeed the very meaning of cooperation, involves the labor of supervision in some form, hence the existence of some authority (not a despotic one). This is only needed for the directing of the process. One can make the despotic aspect of this authority disappear by making the supervisors or managers directly chosen and controlled by the laborers themselves instead of representing capital.” – I think most anarchists would a agree to these principles.

(no authority or centralism but all kinds of councils). It is more of an irrelevant Utopianism of a backward kind. This position was not only impractical an destructive, it was basically anti-democratic; by opposing any kind of authority, even “authority with consent” – This part i just don’t understand. How are counsels (council communism for example) “irrelevant, Utopian, backward, impractical and destructive”. Where is the argument?

(the authority of majority over minority) it upheld the right of a small minority to impose its conceptions upon the majority, even by violence. This is exactly the what Bakunin was to do with the International and his (Bakunin’s) secret Brotherhood by their “Rule or Ruin” creed. – I’m not interested in defending Bakunin (or attacking Marx for that matter). How is this supposed to provide an argument about anti-democratic tendency of anarchism in general?

“By stating that every individual or group should be autonomous the anarchists cannot answer how a society of even two people is possible unless each is willing to give up some of his autonomy. This is a question for which there is no definite answer in the anarchist literature.” – What about autonomy pared with cooperation, solidarity, mutual aid.. just to name a few ideas in anarchist literature

“Is any organization actually possible without authority (or the full autonomy of its members)? Take again for example a factory where the workers decide about the working hours. Whether this is done by a delegate chosen (and able to be recalled) or by the majority of the workers, the individual will (of for example one individual or a couple of them) must subordinate itself to this decision for production to be possible. So the questions are settled in an authoritarian way.” – Maybe you should read some literature on Anarchist Economics. Delegating decisions on a re-callable basis is exactly what anarchist economic organization would look like in my view. I find it strange that you call this “Authoritarian”, it seems pretty democratic and reasonable to me.

To prevent any misuse of the authority given to the decision makers, again whether the representatives or the majority, we can democratize the delegation of authority and make their activities totally transparent. But we cannot prevent some degree of imposing the will of this majority on the specific individual. What we can do, and must do, is to restrict authority within the limits enforced by the necessities of production of social life. If the anarchist is consistent he will even oppose this. But if he is not a lunatic (and we find lunacy in many anarchist movements throughout history) he will have to admit that not every individual Ego can be satisfied.” – Again we agree about decision making. So that means either i and most anarchist are inconsistent? or do you just misunderstand anarchist organization. I’ll refrain from commenting of the last part.

“A truly popular revolution can impose a democratic authority, which of course anarchists oppose on principle.” – Why would a truly popular revolution need a state authority to carry out a revolution. Look at the Spanish Revolution where a popular revolution left the state powerless and irrelevant in many parts of Spain. They already had, and created many more of their own bottom-up direct democratically organized institutions to make the state nothing more than an interference with their own will and inclinations.

“More importantly, we have to realize that autonomy and authority are relative things whose spheres vary with the various phases of the development of society. It is by no means possible to do away with them right after the revolution. Only by an development of society towards the end of class antagonisms it is possible that those “evil” things could be done away with. But to go on the details would be mere speculation. It is up to the future man to accomplish this task, not our fantasies.” – Class is not the only kind of domination in society, and to say that the rest would “wither away” after class oppression has ceased is naive at best, to say nothing of historically unfounded. (you may be able to think a few examples)

2.2 – As I stated before I’m not very interested in Bakunin’s actions. Nor would it serve a purpose to counter pose, Marx, Lenin or Trotsky’s lesser moments.

“If the state is the source of all social ills” – This isn’t anarchist theory, nor has it ever been. The rest of the paragraph just seems irrelevant after that fact.

“The alternative of the present day anarchist, is the breaking up of society in small groups, communes, councils etc. which in turn form an “association” but not a state. What the difference is theoretically, no one knows.” – Who’s “breaking up society”, but anyway. The difference would be it’s characteristics.. bottom-up, direct democratic, federalized, based on solidarity and mutual aid. As you say, the name doesn’t matter, but if that is your idea of a socialist state then we just disagree on revolutionary tactics: Anarchist: don’t try to reform the state, make it irrelevant with it’s own institutions. Marxist: use the state and change society with it. Anyway this is a long argument, and maybe worth talking about with some concrete examples

These are nothing more than the idealist fantasies of the “libertarians”, and nothing more remains to be said about this vulgar, simplified and caricaturist conception of society. – …..I’m not sure if anarchists are the ones doing the caricaturing in this article.

“The new dimension which anarchism gave to the discussion was the discussion of authority, which should be abolished in all of its manifestations.” – as said before, this isn’t the goal of an anarchist.. which is to identify forms of illegitimate authority and abolish it.

For the Marxist on the other hand the “abolition of the state” could about only at the end of a sufficient period of socialist reconstruction of society. So when a socialist government takes power, even in its most democratic form possible, the consistent anarchist must seek its instant destruction as an “authoritarian” menace. – How exactly is the “dictatorship of the working class” “the most democratic form of state possible”? To quote an Martin Buber: “One cannot in the nature of things expect a little tree that has been turned into a club to put forth leaves.” In short, is the socialism created by a centralized state controlled by a party the kind of socialism that we would all like? History i believe comes down closer to Bakunin’s and prediction’s and left Marxist views about the nature of a socialist state than authoritarian Marxists like to admit.

Secondly, for Marxists the aim of the socialist movement is the democratization of political authority, indeed of all authority. For an anarchist, any and all authority, however ideally democratic, has to be destroyed. – As mentioned this is just not true

For Marxists, the abolition of state power does not necessarily entail the elimination of all kinds of authority (for example the authority of the head-engineer of the railroad, or the head surgeon of a hospital) in political and social life. But it is possible for society to evolve in the direction of the diminution of authority in general. – I can’t remember the specific anarchist, but i remember reading something along the same lines (about authority of the baker).

Last but not least, the difference of anarchism and Marxism lies in the definition of freedom. For the anarchist freedom is basically individual-solipsistic: it depends on the absolute inviolability of the sovereign Ego in relation to the outside world; it is the total impermissibility of any imposition of any authority. So anarchism is basically solipsism, whether or not the individual anarchist recognizes this consciously (as I am of the opinion that many anarchists do not). Freedom does not mean freedom through democracy or freedom in society, rather freedom from any democratic authority and in the end freedom from society. – This argument follows (vaguely and unconvincingly) from the premise that anarchism is anti all and any authority – which has already been refuted… so i won’t go into it.

The Marxist view of freedom is basically social in its reference. Freedom depends on the relation of the individual to his membership in the human species, which is historically organized in a society. Freedom is than the democratic freedom in society. This means that the relationship of the individual to the collectivity will involve the maximum extension of control from below. This control applies also to the determination through democratic institutions of the extent or degree to which the collectivity of society should exercise any control over its individual components. – nicely put, i think anarchist would ascribe to this description.

In conclusion, for Marxists (classical)anarchism is not a beautiful vision of saintly dreamers but a sick social ideology. Not only impractical but dangerous in certain contexts (like when there is an actual workers government established). To the anarchists we have only, in the words of Plekhanov, this to say: “You will remain what you are now… bags emptied by history.” – A consistent conclusion, it’s befits the quality of argumentation and unnecessary tone of of the rest article.

First, I will shortly react on Arjan. You are totally right that it doesn’t matter when it comes to common aims like the homeworkers. My essay isn’t about working together, but on fundamental theoretical questions which have in the past (and probably in the future) come up and mark a fundamental difference between these two ideologies. What ASB is doing right now is respectable and I, as a member of KSU, totally support them. Again this essay is about classical anarchism which shares some of the assumptions of present day anarchism but in no way meant to be representative of anarchism after Bakunin.

Now a reaction on Jeremy. About my fundamental misundertandings of anarchism. As you propably know, there is no fundamental understanding of any ideology. If history has shown us anything, it would be plurarity of perspectives. I am not defending the total relativism of the postmodernists, but they are right only in this respect. So my understanding of anarchism, as the history of the anarchist movement itself shows (look at the variations: from anarcho-capitalism to anarcho-syndicalism to even anarcho-primitivism) needn’t be the same as yours.

.

But more fundamentally, as stated in the introduction, this essay is about the ideas and practices of the starting years of anarchism. What is important for the second part (which I hope to finish this summer) is that some of the assumptions, on a general level, are common in many left-anarchist movements. In fact my conclusions are ONLY based on the on the writings of Godwin, Stirner, Proudhon and Bakunin, and the latters anarchist experiment. But lets get back to your internal critique.

It is not the place her to say why the anarchist approach is false. There are many examples of writers with internal and historical critique on anarchism, from Marx, Engels and Plekhanov to present day writers like Hobsbawm. If you are intersted I can come up with a list of written material on the falsity of the anarchist approach.

You say that the Bolshevik party didn’t have anything to do with the working class movement. Again this will be a long discussion to do on a website as a reaction. But yes the bolshevik party represented far greatly the working class movement of Russia in 1917 than any anarchist (mostly agrarian, backward, ignorant groups) groups during the revolution. But lets discuss this matter in another essay or in real live. It is an interesting one but not relevant for our present discussion

When I talk about democracy, I in no way mean the liberal democratic version of democracy. In fact in my opinion it is the dictatorship of the proletariat which is the most democratic form of governance (and no not the dictatorship of the party). And yes when most of the Marxists talk of democracy the do mean the will of the people. But it is the working majority of society, the creators of all wealth, and not the possessors of the means of production. So the meaning of “complete democracy exercised in completely democratic fashion” means a thourough workers democracy. I was of the opinion that this would be obvious to the trained reader. But I was wrong.

About the answers of the anarchist thinkers. There is still in my opinion no real answer to the elementary question, even by Kropotkin or Bookchin. If my opinion is the result of my lack of knowledge, I invite you to enligthen me (and with me many others) on this issue. Buidling institutions on the abstract, semi-utopian concepts of solidarity, freedom or mutual aid is still in the realm of abstraction and implicitly recognizes the magic unanimity of the participants. It is actually even weirder that these anarchists want this institution INSIDE the current society which would make the task much more difficult. Still no satisfying answer is to be found by the hands of these writers.

You say: “Have you heard bottom up direct democracy, federalized on organized on a larger scale with recallable “representatives”. A model that many left Marxists would adhere to as well.” yes indeed I have heard of them. But again I would like to remind you that I am talking about classical anarchism with its Proudhonian Stirnerism which was personified by Bakunin and indeed many times demanded the abolition of all authority.

“This part i just don’t understand. How are counsels (council communism for example) “irrelevant, Utopian, backward, impractical and destructive”. Where is the argument?” I don’t know how the discussion is bend towards council communism, as councils is not synonymous with council-communism. My point is that with the immediate abolition of all central institutions, justified to bring man to his natural state, is indeed a backward Utopianism, because it resembles the feudal european society of small communities with liitle to non central national institutions. And yes when anarchism would be (as it was in its classic form) against authority even with consent (what I even see today when anarchists criticize other groups for this very fact) then anarchism has the potentiality of becoming destructive (as again it was in for example in Russia during the civil war).

“Maybe you should read some literature on Anarchist Economics. Delegating decisions on a re-callable basis is exactly what anarchist economic organization would look like in my view. I find it strange that you call this “Authoritarian”, it seems pretty democratic and reasonable to me.” First, for the tenth time, in my essay my focus is on classical anarchism. Second, having delegates on a re-callable basis is in fact a marxist category later adopted by anarchists. Thirdly, one of my points in the essay is exactly your last sentenc, and why it is false. By authority we mean the imposing of the will of one on another, albeit a democratic one with consent. It is anarchism which has turned the concept of “authority” towards something which it is not in principal, namely despotism. So democratic authority is possible.

“Why would a truly popular revolution need a state authority to carry out a revolution. Look at the Spanish Revolution where a popular revolution left the state powerless and irrelevant in many parts of Spain. They already had, and created many more of their own bottom-up direct democratically organized institutions to make the state nothing more than an interference with their own will and inclinations.” My point is that the very act of revolution itself is the imposing of authority, in fact it is one of the most authoritarian acts in history. And I am not talking about a state but indeed for the revolution to succeed, the revolutionaries have to impose their will upoin the opponents in order to survive (that is why every revolution in history is followed by a period of terror (hopefully I don’t have to explain what I mean by terror in this context) against the counter-revolution). And indeed, the Spanish Revolution didn’t succed (because of many complex factors of cours) and in reality it was a civil war which is not exactly the same thing as a revolution of which I am talking about. But this is the topic of my second essay, so I will be back on that.

“to say that the rest would “wither away” after class oppression has ceased is naive at best, to say nothing of historically unfounded. (you may be able to think a few examples)” As I have mentioned in our private talks, and I hoped it was already clarified, what I mean by class-anatagonisms has not only a economical dimension, but also a cultural, ideological, patriarchal etc. which are all forms of domination (a better concept for it would be contradictions of the capitalist system). But I am now learning to be more specific on these concepts, but this would make the future essays longer.

“”If the state is the source of all social ills” – This isn’t anarchist theory, nor has it ever been. The rest of the paragraph just seems irrelevant after that fact.” This is in fact the basis of classical anarchism, and many other socialist movements of ninetheent century and it still is one of the dominating, albeit an unconcious one, assumptions of many anarchists with whom I have had discussions or anarchist thinkers which I have read.

“How exactly is the “dictatorship of the working class” “the most democratic form of state possible”?” If you read my sentence well, you would have noticed that I say: EVEN in its most democratic form possible, and not that it IS the most democratic form of a state. And again by the dictatorship of the proletariat, i.e. the working class, I do not mean the dictatorship of the party. These two concepts have become synonymous by bourgeois propaganda and are taken over by the opponnents of Marxism. But Marx, the first one to use the “dictatorship of proletariat” never meant the dictatorship of the party UPON the proletariat.

“This argument follows (vaguely and unconvincingly) from the premise that anarchism is anti all and any authority — which has already been refuted… so i won’t go into it.” Yes within classical anarchism we find many ideas about authority, but what they had in common was their public denouncement of authority in general. This is a theoretical discussion and something impossible in practice (as I have tried to sketch by the example of the Bakuninist experiment). But it seems to be an implied assumption.

I hope I have achieved some degree of clarification. The above is an fast reaction. For a more thourough analysis’s of Jeremy’s critical notes I would like to ask the reader to have some patient for my second part to be finished. When that would be I dare not to say.

Thanks for this reaction. I’m interested to read the next part. It seems to me there is little disagreement (just lots of misunderstandings), appart from the strategic question of using the state as a revolutionary agent. So maybe you can focus more on that.

Kameraden,

Ik kom net terug van een interessante tussenkomst, die de IKS samen met de ASB heeft gedaan, in een protestmanifestatie in Den Haag tegen de maatregelen van de kapitalistische staat ten aanzien van de gezondheidszorg er de verzorging. Maar

toch wil ik even een niet al teveel ontwikkelde reactie geven op de discussie die jullie hier voeren over marxisme en anarchisme. Misschien kom ik er later wat uitvoeriger op terug.

Ik wil jullie even refereren aan een discussie tussen ravachol en rgfront , die vorig jaar november plaatsvond op Revleft, en die ook een heleboel punten aansneed en uiteindelijk eindigde in een zekere blokkade tussen beide. Ik heb getracht die discussie weer op te pikken middels de volgende bijdrage. Ik had op heel veel punten kunnen reageren, net zoals ik dat nu ook kan doen (bijvoorbeeld: kan je spreken over HET ANARCHISME? , iemand als Domela Nieuwenhuis, had ondanks zijn wat warrige denkbeelden in de latere jaren van zijn leven, zijn hele leven tot het proletarische kamp behoort omdat hij een onvoorwaardelijk internationalisme bleef.

In ieder geval had Plechanow op dat moment wellicht gelijk, maar Bakoenin met zijn Geheime Alliantie en zijn parasitair gedrag, had dan ook enorm veel kapot gemaak binnen de Ie Internationale

Vorig jaar november (2010) heb je op RevLeft een discussie gevoerd met rgfront. In je reactie op de argumenten die rgfront aanvoert, stel je op een bepaald moment “….. niemand pleit voor ‘democratie’ daar waar de klassenmaatschappij nog bestaat. De vernietiging van staat en kapitaal heeft niks te maken met ‘democratie’, maar dit betekent niet dat er in de nieuwe orde, de statenloze, klassenloze maatschappij, die daarvoor in de plaats komt, geen sprake is van ‘democratie’ in de zin van egalitaire, horizontale overleg processen.

De discussie tussen jou en rgfront beperkt zich niet tot de kwestie van de democratie, maar ik stel voor om, in de eerste reactie mijnerzijds, niet onmiddellijk alles aan de orde te stellen. Laten we beginnen met te stellen dat de discussie over ‘democratie’ een moeilijke discussie is. Want aan de ene kant vertegenwoordigt de huidige parlementaire democratie binnen het kapitalisme de politieke vorm van dictatuur van het kapitaal. Maar aan de andere kant spreken de linkskommunisten zelf, naast de noodzaak van een dictatuur van het proletariaat over de voormalige heersende klasse en over iedere opnieuw verschijnende staatsvorm, ook regelmatig over arbeidersdemocratie en soms zelfs over radendemocratie, als het gaat over verhoudingen binnen de arbeidersklasse in het kommunisme. Dat wij, zoals jij dat noemt ‘horizontale’, ‘egalitaire’ maatschappelijke verhoudingen moeten opbouwen binnen het communisme is duidelijk. Als je dat democratie wilt noemen, dan is dat best begrijpelijk. Maar er is en blijft wel een fundamenteel verschil tussen de democratie van het kapitalisme en dat van de kommunisme. En dit beperkt zich niet alleen tot het feit dat de ‘democratie’ van het kapitalisme een ‘hiërarchisch’ karakter heeft en de democratie van het (anarcho-)kommunisme van nature’egalitair’ (of bottom up) is. Het heeft ook te maken met het feit dat de ‘democratie’ van het kapitalisme atomiserend en vervreemdend en manipulatief werkt en in feit de onderdrukking en uitbuiting sanctioneert.

Om je duidelijk te maken wat het verschil is tussen een ‘dode’ democratie en een ‘levende’, wil ik een citaat aanhalen uit Internationalisme/Wereldrevolutie dat geschreven is naar aanleiding van de meest recente gebeurtenissen in Spanje, waarin de Algemene Vergaderingen, de meest duidelijke, pregnante vorm van directe democratie en zelforganisatie van de klasse, een centrale rol speelden:

“De Algemene Vergaderingen gaan terug op de proletarische traditie van de Arbeidersraden van 1905 en van 1917 die zich, tijdens de wereldwijde revolutionaire golf van 1917-1923, uitbreidden naar Duitsland en andere landen. Later doken die weer op in 1956 in Hongarije en in 1980 in Polen” De gebeurtenissen op de Puerta del Sol in Madrid in Spanje toonden wel heel duidelijk hoe de ‘armoedig’ de burgerlijke ‘democratie’ afsteekt bij de democratie van de arbeiders en andere niet-uitbuitende bevolkingslagen.

“In de burgerlijke democratie berust de beslissingsmacht bij een bureaucratisch korps van beroepspolitici, dat op zijn beurt zonder tegensputteren de orders van de partij opvolgt, en dat enkel en alleen een verdediger en vertegenwoordiger is van de belangen van het kapitaal.

Bij de Algemene Vergadering daarentegen ligt beslissingsmacht direct bij de deelnemers die samen nadenken, discussiëren en beslissen en het zijn zijzelf die zich organiseren om de besluiten om te zetten in de praktijk.

In de burgerlijke democratie wordt de individuele atomisering gesanctioneerd en versterkt, en is de concurrentie en de opsluiting in het ‘ieder voor zich’ het kenmerk voor deze maatschappij. Bij de Algemene Vergaderingen komt een proces op gang van collectief nadenken, waarbij iedereen het beste van zichzelf bijdraagt. Iedereen kan de gemeenschappelijke kracht en solidariteit aanvoelen, er wordt een omgeving geschapen waar het tegengif wordt gebrouwen tegen de verdeelde en de verscheurde vorm van de kapitalistische maatschappij. Daar worden de grondslagen gelegd voor een nieuwe maatschappij, die gebaseerd is op de afschaffing van de uitbuiting en van de klassen, en die kan leiden tot de opbouw van een menselijke wereldgemeenschap. (…)

Wat is de sfeer van een verkiezingsbureau, waar de ‘burgers’ in stilte aanschuiven, dan toch zielig: alsof zij een plicht moeten vervullen waarvan zij het nut betwijfelen en waarbij zij zich schuldig voelen over de uitgebrachte stem die altijd ‘verkeerd’ blijkt te zijn!

Wat een verschil is dat met de sfeer van emoties die wij beleven bij de Algemene Vergaderingen! Men merkt in het grote enthousiasme een enorme zin tot deelname. Talloze sprekers maken gebruik van de kans om het woord te nemen om allerhande vraagstukken aan te kaarten. Wanneer de Algemene Vergadering is afgelopen, worden er commissievergaderingen gehouden, die 24 uur per dag doorgaan. Er worden contacten gelegd, mensen leren elkaar kennen, er wordt hardop nagedacht, alle aspecten van het politieke, sociale, culturele en economische leven komen aan bod.

Men komt tot de ontdekking dat men kan praten, dat men alle zaken collectief kan behandelen. Op de bezette pleinen worden bibliotheken opgezet, men organiseert een ‘tijdsbank’ om les te geven over allerlei thema’s, zowel wetenschappelijke als culturele, artistieke, politieke als economische. Er worden gevoelens uitgedrukt van solidariteit, er wordt aandachtig geluisterd zonder dat iemand zich opdringt, een bedding van algemene empathie. Op een nog schuchtere manier wordt er op die manier een massale debatcultuur in het leven geroepen. Veelvuldige overdenkingen, dikwijls interessante voorstellen, ideeën van allerlei slag, het lijkt alsof de deelnemers publiekelijk hun gedachten willen overbrengen, die zij gedurende lange tijd herkauwd hebben in de eenzaamheid van de atomisering. De pleinen worden overspoeld door een reusachtige en collectieve storm van ideeën, de massa slaagt er in het beste en diepste van zichzelf tot uitdrukking te brengen. Die anonieme mensenmassa, die verondersteld wordt, de verliezers te zijn in het leven, beschikt over onverwachte reusachtige en diepgaande intellectuele bekwaamheden, actieve gevoelens, sociale emoties.”

Ik stel me zo voor dat deze bijdrage niet meteen alle verheldering zal brengen over de kwestie van de ‘democratie’. Want de kwestie van de democratie is inderdaad iets dat niet al te gemakkelijk te doorgronden is. We moeten ons bewust zijn dat het fenomeen democratie namelijk ook een heel misleidend karakter heeft. Ze kan een beweging, in plaats van de kant van het anarchisme c.q. communisme, net zo gemakkelijk voeren in de richting van een onmogelijk te verwezenlijken wens en eis als een directe, ‘echte democratie’ binnen het kapitalisme. Dat hebben we ook kunnen zien aan dezelfde gebeurtenissen op de Puerta del Sol: terwijl de “indignados” (de verontwaardigden) op het plein, in de organisatie van hun demonstratie, de vorm overnamen van de arbeiderklasse (algemene vergaderingen, directe democratie, zelforganisatie) was en bleef hun voornaamste leuze toch “Echte Democratie Nu”

Kameraadschappelijke groeten,

Arjan

PS. De IKS heeft in de afgelopen jaren heel veel geschreven over het anarchisme. Maar lees het liefst eerst onze artikelenserie over “De Kommunistische Linkerzijde en het Internationalistisch Anarchisme” (zie: http://www.internationalism.org)

The anti-capitalist movement has always been a plural one, with lots of organizations, ideologies and factions. In the past, most of these groups have claimed to hold the absolute truth. We however are all implicitly familiar with the post-modern critique on ideologies and know that the truth is far more diffuse and that it will certainly not conform to any of our theories. Quite the contrary, we have to make our theories work by studying the truth and by an honest and open exchange of ideas.

Marxism and (some) anarchist traditions have a common goal: the destruction of capitalism through the socialization of the means of production and the political emancipation of the proletariat. It is hard to acknowledge the minor differences and to stay focused on all that these movements have in common. In this respect, the article failed to create a sense of comradery.

However, the article (as written by a marxist) could’nt possibly agree with theorists like Stirner and Proudhon. I read some of the responses to the article which are all in defense of ‘anarchism’. But shouldn’t most members of the ASB and IKS agree with the Marxist critique on Stirner and Proudhon? And yes… even Bakunin? After all his strategies of ‘conspirational putschism’ is an anachronism and is no longer being used. Don’t the ASB and IKS have much more in common with Marx than with Stirner and Proudhon, because as Arjan mentioned above, they are now openly involved in the class struggle in a positive sense.

I think this is a very interesting discussion, but it also shows we are still working to much in an outdated paradigm. The issue is not ‘us’ (marxists/communists) against ‘them’ (anarchists/or whatever), the issue is ‘us’ (working people) against ‘them’ (capitalist exploiters/imperialist warmongers). If we want to create a constructive dialogue we have to let go of that sentiment. It is a destructive attitude that can only create division where there should be unity.

I’m looking forward to the next part of this article, but I hope the writer will refrain from using some of the plattitudes I read here. This could be a very interesting discussion if it were done in the right way (by both sides).

I welcome the contribution of ‘Kahless the Unforgettable. She has put forward some interesting remarks.

Especially where she writes that “The issue is not ‘us’ (marxists/communists) against ‘them’ (anarchists/or whatever), the issue is ‘us’ (working people) against ‘them’ (capitalist exploiters/imperialist warmongers). If we want to create a constructive dialogue we have to let go of that sentiment. It is a destructive attitude that can only create division where there should be unity.”

Let’s be clear: marstists have a critique on Stirner and on Proudhon. Marxists have denouned the ‘conspirational putschism’ of Bakunin. But that doesn’t mean that marxists have denounced them from the very beginning. Marx has for instance shown some admiration for Fourrier, Owen, Saint Simon and also for Proudhon for a short while. They all were representatives of the early stage of the working class history, and it is not up to us to throw them in the dustbin of history, but to comprehend what their respective contributions meant for the life of the working class at the time they lived. An example: when Einstein discovered a better theory than Newton, we don’t immediately say too that Newton was a stupid guy and that he didn’t know what science was. Many of these persons have contributed in on way or another to the historic development of the theory of the proletariat. But almost all of them have been criticized thoroughly until up to the roots of their theoretical conceptions. Only if comrades nowadays still defend the theories, these predecessors of the working class have developed, and still want to base their activities on these theories, we call this: an outdated paradigma.

‘Kahless the Unforgettable’ has completely right that “Marxism and (some) anarchist traditions have a common goal: the destruction of capitalism through the socialization of the means of production and the political emancipation of the proletariat.” It is indeed true that some anarchist traditions have a common goal with marxism. But the other way around is also true: some marxist traditions have a common goal with anarchism. Because not only among anarchist there are some with outdated paradigma, but also among marxists there are some with outdated paradigma. One of the main criteria here is: have these anarchists or marxists betrayed the historic interest of the working class, yes or know. In 1870 many courageous Proudhonnist stood side-by-side with other combative workers, but we have never denounced them because they were adepts of Proudhon at that time. But when Kropotkine (in contrast with Malatesta), during the WWI dit not protest against the butchery of the workers in a war between capitalist states, he betrayed the historical cause of the working class. The same is true for a number of marxist: when Kautsky, Legien, Scheidemann and consorten spoke out in favour of a war against France, and send the fine-fleur of the working class into an endless trench warfare, where most of them were murdered, they betrayed the workers.

The next phrase of ‘Kahless the Unforgettable’ one of the most interesting, because her she poses the question of the scientific method an the necessary culture of debate:

“…. and know that the truth is far more diffuse and that it will certainly not conform to any of our theories. Quite the contrary, we have to make our theories work by studying the truth and by an honest and open exchange of ideas.”

First the question of the scientific method. To give an idea of the marxist scientific method, I refer to a letter from Marx to the editor of the Russian journal Otyecestvenniye Zapisky (November 1877), responding to “a Russian critic” who tried to portray Marx’s theory of history precisely as a dogmatic and mechanical schema. In the letter in question, Marx actually comes to a very different conclusion: “In order that I might be qualified to estimate the economic development in Russia to-day, I learnt Russian and then for many years studied the official publications and others bearing on this subject. I have arrived at this conclusion: if Russia continues to pursue the path she has followed since 1861, she will lose the finest chance ever offered by history to a nation, in order to undergo all the fatal vicissitudes of the capitalist regime”.

In sum: Marx certainly did not consider that his method for analysing history in general could be applied rigidly to each country taken separately, and that his theory of history was not a rigid system of “universal progress”, describing a linear, mechanical process which must always lead in the same progressive direction. Furthermore: his method is concrete and involves consideration of the actual historical circumstances in which a given social form appears. In the same letter, Marx gives an example of the way he works: “…… Thus events strikingly analogous but taking place in different historic surroundings led to totally different results. By studying each of these forms of evolution separately and then comparing them one can easily find the clue to this phenomenon, but one will never arrive there by the universal passport of a general historico-philosophical theory, the supreme virtue of which consists in being super-historical”

The example of the letter shows that Marx insisted on studying a given social formation separately prior to making comparisons, and in this way “finding the clue” to the phenomenon in question; it does not show that Marx refused to go from the particular to the general when it came to understanding the movement of history. Above all, the charge that attempts to locate capitalism in the context of the succession of modes of production is a “super-historical” project is refuted by the approach in the Preface to the Critique of Political Economy, where Marx outlines his general approach to historical evolution, and where he very clearly announces the scope of his investigation.

A second point which I want to underline in this part of the contribution of ‘Kahless the Unforgettable’ is the importance of the culture of debate, in order “to create a sense of comradery”.

In the first draft of his reply to Vera Sassulitsch Marx writes: “This society is waging war against science, against the popular masses, and against the productive forces it creates.” Capitalism is the first economic system which cannot exist without the systematic application of science to production. (….) But today, in the period of decadence of capitalism, the bourgeoisie becomes more and more an uncultivated and primitive class, whereas science and culture are in the hands either of proletarians, or of paid representatives of the bourgeoisie whose economic and social situation increasingly resembles that of the working class. The proletariat is the heir to the scientific traditions of humanity. Even more so than in the past, any future revolutionary proletarian struggle will necessarily lead to an unheard of flourishing of public debate, and the beginnings of the move towards the restoration of the unity of science and labour, the achievement of a global understanding more in keeping with the demands of the contemporary age.

Before concluding my short contribution with a phrase of ‘Kahless the Unforgettable’ I must be clear on the fact that, even if I defend internationalist anarchism against nationalist marxism, I am in the first place a marxist and not a anarchist. If I have the tendency to defend ‘anarchism’, then this must be seen in the context of the cooperation between the ASB, KSU and IKS to publish and distribute a declaration of solidarity with the struggle of the Thuiszorgerwerkers in particular and the working class in general . The moment which was chosen to publish this first contribution against the anarchist was therefore not a very well chosen moment.

The conclusion of ‘Kahless the Unforgettable’ that the article: A Marxist critique of Anarchism. Part one: the foundations of anarchism “failed to create a sense of comradery, is completely right. If we want to create a constructive dialogue we have to let go of that sentiment. It is a destructive attitude that can only create division where there should be unity. I hope the writer will refrain from using some of the plattitudes I read here. This could be a very interesting discussion if it were done in the right way (by both sides). Even”If may be is hard to acknowledge the minor differences and to stay focused on all that these movements have in common.”

Arjan

PS: Can this discussion not be put on a more central place on the website of the KSU?

Recently, a member of the ASB wrote a critique of this polemic which can be found on the ASB website here: http://anarcho-syndicalisme.nl/wp/?p=1052

Sad article, very disappointing to read. First, there is the tone of absolute, rather arrogant, dismissal of anarchist theory, even a refusal to give arguments for this attitude. Example: “Implicit within this approach is that the state precedes society and class structure, not the other way around. There is no need to explain why this approach is false, because it has been done by many writers.” Not only is – so Poejesh says – the anarchist position “false”, the need to actually show that it is “false” is dismissed. But if everybody already knows how ridiculous anarchism is, why write a long article on it? Why argue with a theory that is so evidently a “sick ideology”, held by “bags emptied by history”? By the way, is that Poejesh’ idea of comradely debate? Insulting the ones whose ideas you, rightly or wrongly, reject? Would he like to be shouted back like that? Or would he like some respect? I am willing to grant him the latter, but he does not make it easy.

Then, there is the lack of evidence. Lots of things are said about poor old Proudhon and Stirner, both seriously misrepresented, and Bakunin, taken out of his historical context. No quotes are given, no sources are mentioned. In fact, the only quotation is by the marxist Plekhanov, out of a polemical article against anarchism that even marxist Lenin found totally over-the-top in its one-sided hostility. See his “The State and Revolution”, you can find it at http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1917/staterev/ch06.htm#s1 See? Giving evidence for what one says is not that dicfficult. You can do it too!

I will not mention here all the untrue statements in the article, neither will i show why they are untrue (he does not prove his points, so why should I?). Maybe another time, another place. Two other things I cannot just let go here. First is the evasion in his reply to Jeremy’s – wonderful, cool, calm and collected! – criticism. Poejesh says: “As you propably know, there is no fundamental understanding of any ideology. If history has shown us anything, it would be plurarity of perspectives. I am not defending the total relativism of the postmodernists, but they are right only in this respect. So my understanding of anarchism, as the history of the anarchist movement itself shows (look at the variations: from anarcho-capitalism to anarcho-syndicalism to even anarcho-primitivism) needn’t be the same as yours.” What?!? In the article he is quite sure how wrong,bad, evil, harmful, nay SICK thi anarchist ideology is. But suddenly there is this friendly let’s-agree-we-can-disagree “plurality of perspectives”… What is it? Am I, or am I not, a “bag emptied by history”? A bit of clarity would be nice here…

Last thing: Poejesh presents an internal inconsistency, even in his reaction to criticism. First he says: “In fact in my opinion it is the dictatorship of the proletariat which is the most democratic form of governance”(sixth paragraph of his reaction). Fine. But in the 13th paragraph he says, about the dictatrshi of the proletariat: “If you read my sentence well, you would have noticed that I say: EVEN in its most democratic form possible, and not that it IS the most democratic form of a state.” Now, is, or is not, that dictatorship of the proletariat, the most democratic form of governance, according to Poeiesh? The whole thing smells of muddled thinking, ore out of hostility to anarchism than because of inability to think clearly. Ability Poejesh surely has, plenty of it. Why then does he put it to such a hostile, distorting, uncomradely use?

A small thing to finish with. I am impressed by how Arjan de Goede – with whom I have disagreements, as h and I know well – is taken part in this debate: respectfully, comradely, trying to prove his point, not just to make it. It can be done. It should be done. Even, nay especially, where we strongly disagree.

Dear Peter,

First of all about the tone. My tone is not meant arrogantley but I intend to absoluteley dismiss classical Anarchism as a workable theory. So to all who think that it is not constructive, you are right, because it is intended to be destructive, but mereley the theoretic part. It is not intended to insult anarchists around me for whom I have the greatest respect; with whom I work together a lot and the fact that we encounter each other so often means that we have much in common. It is only destructive in the sense that it is intended to do away with the myths created by and surrounding anarchist thinkers. This due to the attractiveness of these myths and rhetorics among young people like myself.

Secondly, the reason why I not discuss extensively the falsity of anarchism historically, (which I try to do theoretically with the classical anarchist thinkers) has to do with the amount of time and space. But there is indeed a great body of work written from the marxist perspective, even outside this perspective, about anarchism’s falsity: from Marx and Engels, to Plekhanov, Lenin…. even contemporary Marxists like Hobsbawm.

About the lack of evidence. As my intention wasn’t to write an academic article I didn’t put any footnotes or references and now I see that it was wrong not to do this. I merely accepted that many of the anarchists, to whom the article is directed, know the history of for example Bakuninism and the International or Stirner’s writings etc. As for the so called facts that I have mentioned you can search for them yourselves, whether Stirner just watching the 1848 revolution going by or Bakunin wanting a secret dictatorial brotherhood etc. If really needed I can re-edit my article with many references to written historical material. Quotation is not the basic of evidence, as it isn’t even done in many academic writings which you yourself would accept as accountable. And yes giving evidence isn’t that difficult but it tends to make the article in the wordpress-fromat chaotic. So it was a deliberate choice, not a lack of knowledge about how to do it.

About various interpretations. Indeed, how hardly one tries to refuse to accept this, the reality remains that variety exists. As in Jeremy’s case, he totally understands anarchism differently than I understand classical anarchism, to the point that Jeremy and me actually agree on 90% of the tactics and strategies. What Jeremy does is intermingling in his respose of my views on classical anarchism with the theories of more contemporary anarchists. By his own understanding of anarchism and his choice of adopting recent anarchist solutions of these historical problems, he is criticizing my article, but the article itself, as mentioned at least ten times, is about classical anarchism and anachism is used for the sake of simplicity as a synonym for classical anarchism. So when I say that it is sick, I really mean that I find classical anarchism, especially the Bakuninist putchist, conspirational form, as really sick, not psychologically (although that may be possible) but socially, as in capable of destroying that which is valuable for the working class.